Voices of Black youth remind adults in schools to listen — and act to empower them

The idea of inviting students into classroom conversations that teach them to define and express their concerns, ideas and opinions takes inspiration from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC).

The right to be heard is the general principle, and Article 12 of the UNCRC provides for children’s involvement in decision-making that affects their lives. It includes the right for children to express their views.

Many educators are increasingly concerned with the representation of student voices in kindergarten to Grade 12 classrooms. In the words of educator Shane Safir: “Educators should view students not as empty vessels for the transfer of information but as knowledge builders in their own right. We need to share influence in the classroom rather than hoard it.”

But this concern is not necessarily adopted by all teachers. Creating dialogue among educators and students, especially Black Canadian youth, regularly proves problematic because of the history of their negative schooling experiences.

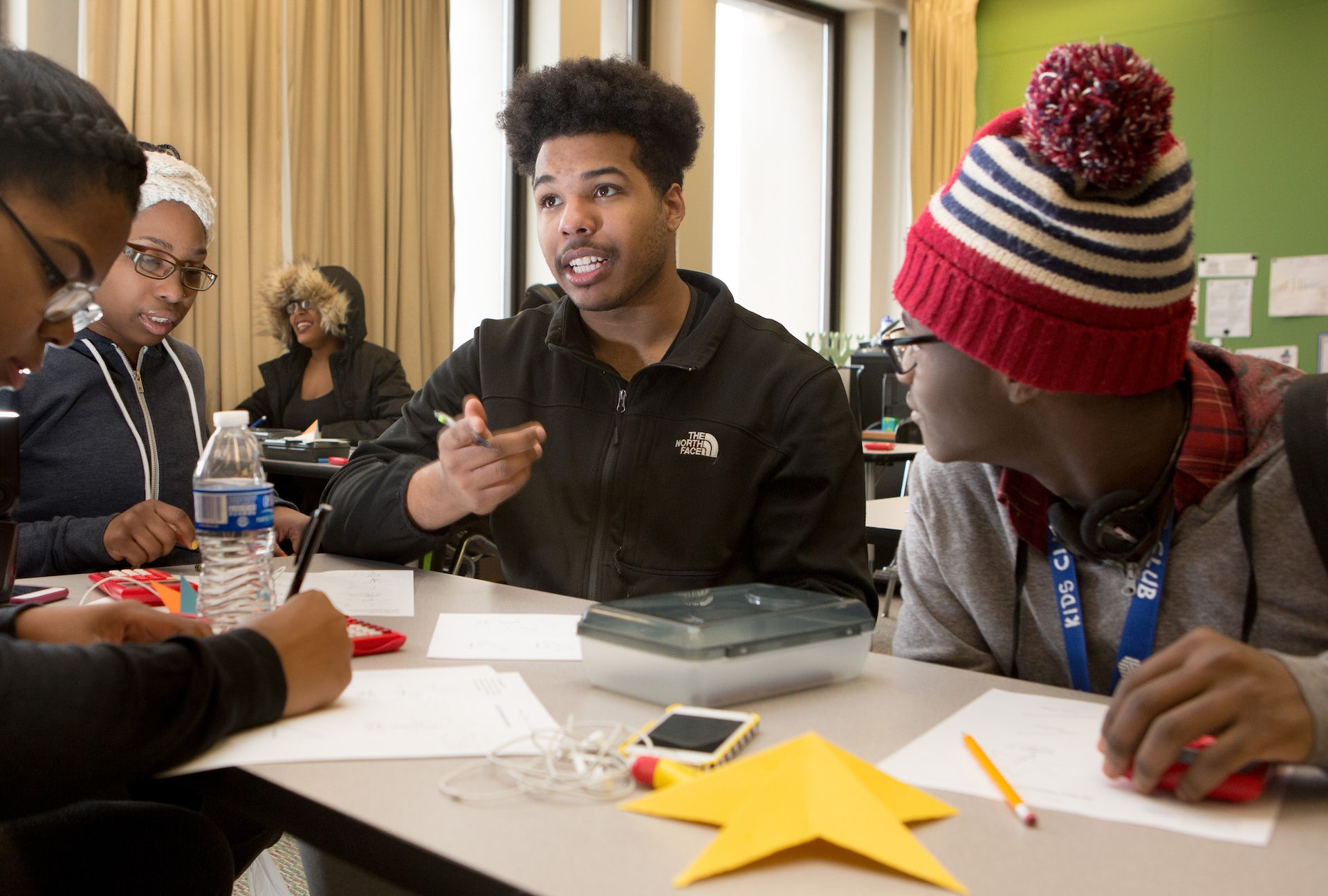

As an education researcher who examines schooling experiences of Black Canadian youth and their families, I have worked alongside Black high school students in grades 10-12 to engage youth voices at the Black Student Summer Leadership Program. This is offered through the Centre of Excellence for Black Student Achievement at the Toronto District School Board.

Youth Participatory Action Research involves youth participating in their communities and in their own education to research issues that affect their lives. It also necessarily implies action on the part of receptive and understanding adults, willing and poised to help bring about changes youth need to see.

Struggles in and for ‘voice’

One of the greatest struggles to allow for “voice” is the role of adults in these interactions and the hierarchical nature of schools. Paying attention to student voice involves changing fundamental values, norms and institutional practices, which means teachers need to be open to this shift.

The term youth voice has gained credibility since the early 1990s. Scholars and education researchers challenged school staff to stop seeing youth as passive recipients of an education. “Youth voice” describes the many ways youth might have opportunities to have a voice and active participation in decisions shaping their lives.

Positioning Black students as learners and collaborators will require a shift in educators’ attitude towards them. That is, changing perceptions that see them as a threat.

Educators need to acknowledge stereotypical perceptions of Black people and communities that often inform how schools and teachers interpret Black students’ behaviours, and get to know Black students beyond their academic or extra-curricular achievements.

Black youth’s whole selves

If schools desire genuine opportunities for students to be heard, educators must see Black youth as their whole selves. Teachers who view the validity in sharing power in classrooms will actively seek Black students’ input. This must be done outside of the formalized structure of student councils or associations where students are elected to represent student communities.

Change is needed in the way Black students’ voices are positioned in education, bearing in mind:

- Black youth are not voiceless. They should be able to inform decisions. To include students’ input in the decision-making process fosters their growth and development.

- There are many ways youth exercise their voices among their peers. For Black youth to negotiate education spaces safely, they often choose how to amplify their voices, including what to say, when to speak up and who to address.

- Educators must remember they (we) are not granting Black students the ability to speak. Rather, we must strive to create classroom and school environments where Black students’ voices and ideas are welcomed and respected.

Youth Participatory Action Research

When Black students work in an environment where they feel safe to express their concerns, this creates avenues for them to build transferable skills (like writing, community activism, research, public speaking and so on).

The TDSB’s Black Student Summer Leadership Program was originally created in 2019 through a partnership with the Jean Augustine Chair at York University, with graduation coaches for Black students at the helm. Since then it has evolved with the support of other departments at the board. Black students involved in this program gain leadership opportunities and positive relationships with adults and their peers while participating in research.

Participatory action research has been associated with revolutionary educational projects. It’s inspired by the work of education scholar Paulo Freire who wrote about popular education as a way of raising people’s consciousness and empowerment.

Youth as co-researchers

The principle of Youth Participatory Action Research includes adults sharing the space with youth as co-researchers, sharing ownership in decision-making and supporting and empowering youth as agents of change. It is inquiry based. Topics chosen by students are grounded in their lived experiences either in school and community.

Together, or individually, Black students have learned how to engage in participatory action research using an Afrocentric research paradigm. For research to be relevant to Black students in the summer program, they learn to use methods and choice of presentation tools that embodies their creativity, skills, lived experiences and intersecting identities.

Black students learn how to become submerged in their own research, rather than experiencing themselves as the object of others’ research.

What shapes education

Youth Participatory Action Research provides Black students with opportunities to discuss what shapes their education. In the summer program, Black students present research projects to education stakeholders.

Their findings include sharing practical solutions based on their experiences negotiating things such as: anti-Black racism, lack of representation in curriculum, mental health and well-being, student-teacher interactions and relationships, linguistic or hair discrimination and newcomer experiences.

Among their recommendations are carefully outlined considerations for school improvement efforts. For example, students have called for providing ongoing professional development training for teachers and school staff that is culturally relevant and responsive to Black students’ well-being and needs. Some research has highlighted the need for more accountability from staff, based on examining policies to protect their rights as students so they may be successful.

In order for change to be implemented, key decision makers need to be willing to engage youth and to act. Authentically empowering student voice requires that educators listen, validate youth knowledge and experience, and respond.

A promising approach

Youth Participatory Action Research is a promising approach for creating avenues to support Black students’ self-determination and agency.

Amplifying youth voice in alignment with the mission and values of school communities is significant for an empowered path forward. Such a path does not see decisions being made for and about Black student lives as an afterthought.

Rather, as outlined in the UNCRC, commitments to participatory action research acknowledge Black youth as competent to act, experts in their own daily lived social realities.

Tanitiã Munroe is a PhD candidate in OISE's Department of Leadership, Higher and Adult Education and a senior research coordinator at the Toronto District School Board. This article originally appeared in The Conversation.